Ikon Gallery, Birmingham | 21 September – 13 November 2011

Fondazione Galleria Civica, Trento | 8 October 2011 – 5 February 2012

S.M.A.K., Ghent | 27 February – 3 June 2012

Museu Serralves, Porto | 13 July – 21 October 2012

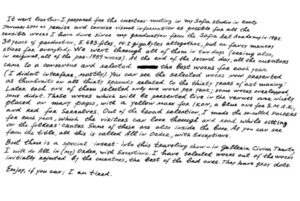

Nedko Solakov’s handwritten text on the front of the gallery guide

The democratisation of information made possible by the exponential growth of communication networks is a critical mechanism in new global power relations, described by Hardt and Negri as Empire[1]. Populations and communities are becoming increasingly empowered to call for and expect transparency from those in power. The pace of change in information access might explain why many arts institutions are examining their practices and seeking to respond to this new order.

After major expansion in arts provisions under the Labour Government during the 1990s, the recent global economic decline and consequential austerity measures has left the arts desperately trying to justify their funding. In this climate the earlier investments in the arts demands higher public benefits, or at the least question their purpose and values. This has added urgency to the work taking place over the last decade where art institutions have instigated self-reflective frameworks, in the form of symposiums, events and publications, to rigorously assess the role of the art institution. These discussions have rarely aimed to directly engage broad audiences; participation in debates has mainly focused on specialist art circles and could easily be accused of institutional navel-gazing. In parallel, the shifting, hybridisation and increasingly interchangeable roles of the artist, curator, critic, activist, etc., has posed art institutions with the challenge of how to represent this contemporary condition to a lay public.

All in Order, With Exceptions, Nedko Solakov’s largest retrospective to date, on display at the Ikon Gallery (Birmingham) in autumn 2011 plays on this discourse. The touring exhibition makes transparent through its four different editions the subjective curatorial processes of exhibition making and the influence this has.

A handwritten message by the artist on the front of the gallery guide, declares to the audience the strict parameters that he has set the curators of the Ikon, S.M.A.K. (Ghent), and Museu Serralves (Porto) to work within. This Brechtian direct-address is typical of Nedko Solakov’s practice; his personality and satirical voice are at the core of his work, establishing an intimate repartee with the viewer. Having spent much of his life under Communist rule in Bulgaria, his work reflects his sensitivity to and perceptions about political and institutional power, as well as his scepticism of the institutional authority that prevails within the art world, ‘constantly echoing his internal struggles between his eagerness to collaborate and his refusal to be manipulated’[2]. In this exhibition, his voice transcends individual artworks to the gallery space as a whole and – having specified no other captions or wall text – bypasses the curators mediation, to narrate the exhibition directly to the audience.

Providing the curators with ‘as precise and concise visual information as possible for all the sensible works’, Solakov asked the curators to reach a consensus on the ‘best works’ from each year since his graduation from Sofia Art Academy in 1981. [3] Each institution would later individually select one work from each year to exhibit. He has documented this process, including images of all shortlisted works, in a new work, The Folders (2011), exhibited at each venue; his narration through the filed pages renders the curatorial processes (and his opinion on them) explicit.

Solakov’s deliberate use of the word ‘best’ in his opening statement suggests that selection is objective, beyond the curator’s personal opinion. As J.J. Charlesworth has written ‘Institutions appear merely as passive presenters of what is ‘best’ or ‘most innovative’ in artistic practice, while obscuring or hiding the fact that institutions make choices about what not to present, exerting power over how artistic practices are made visible’[4].

Visitor looking through The Folders (2011) at Ikon Gallery (Birmingham)

Boris Groys’ analysis of this curatorial power is interesting to introduce here. Whilst he acknowledges artists’ skepticism of the iconoclastic nature of curating, he uses the etymology of curating to liken it to ‘curing’, and subsequently suggests artwork is sick and helpless – ‘a spectator has to be led to the artwork, as hospital workers might take a visitor to see a bedridden patient’[5]. In doing so however, the curator inevitably contextualises and narrates works of art, therefore curatorial practice can never entirely conceal itself. Therefore Groys proposes that the main objective of curating must be to visualise itself, by making its practice explicitly visible.[6] Solakov exemplifies this theory, and utilises these tools of narration and mediation precisely to undermine the curatorial process, liberating his position and the artworks within the institutional framework.

Despite the three curators having come to a consensus for the shortlist, the inevitable multiple-authorship[7] specific to any gallery space would lead to the three exhibitions being significantly different, both in final selection and contextualisation. Furthermore, the exhibition title takes on a sense of irony, since the works follow no particular sequence but are instead left up to the curator to position. The works are in an order, but they could equally be in an infinite number of other orders. The fourth edition of the exhibition, All In (My) Order, With Exceptions, selected by Solakov himself from those works ‘initially rejected by the curators, the best of the bad ones’[8] and the installation of Insolent Art, above the front desk at S.M.A.K, which will declare Solakov’s ‘disappointment with the first venue’[9], suggests a curatorial influence from radical democracy, where multiple viewpoints, including the artist’s own, are encouraged to instigate constructive debate[10].

However, most visitors will only see one version of the exhibition. If this was the only experience of the project it would undermine Solakov’s efforts to exhaustively present his practice and would run the risk of falling into the same ‘inner circle’ trap where only those with special knowledge would see the varieties he seeks to highlight.

The Folders (2011) therefore is the fulcrum of the entire exhibition. Three crates, containing thirty-two files documenting all the shortlisted works in chorological order, act as stimulus to his core curatorial concept. For each year there is a screenshot of the list presented to the curators; rejected works are highlighted and a marker placed next to those chosen for exhibition at each venue. The disclosure that there are only three works which overlap in the curator’s selections, highlights to the audience the subjectivity and partiality of the retrospective they are viewing.

A cushion and a pair of white gloves sit on top of each of the open crates, evoking both formal and informal examination of the contents. The viewer is invited to browse through the numerous pages depicting hundreds of works, annotated by hand throughout with relative political and personal historical facts, ponderings on the exhibition development and curatorial decisions, diagrams and doodles. The intimacy of the work is pivotal to the exhibition experience for the visitor and is animated by their presence. Intending to create a situation where visitors can engage with his work on many different depths of exploration, the visitor takes on a performative role of researcher, archivist or curator as Solakov subtly choreographs their activity.

Insolent Art #6 (2007) installed at Kunsthaus Baselland, Basel. Each time the work is installed a new site-specific phrase is added between the parentheses.

The encyclopedic quantity of information that Solakov provides in the exhibition is almost impossible to comprehend in its entirety. The hefty, high-production catalogue that accompanies the exhibition, provides a comprehensive overview of the works at all four venues in chronological order. However, many of the works vary depending on thier location, for example Toilets (2006), and the written narration in The Folders and throughout Solakov’s self-curated show in Trento was too extensive to include. Whilst the catalogue will inevitably be the key historical record, its rigidity and finality is somewhat contradictory to the entirety of the exhibition. In context it is only one tool of taxonomy and representation amongst many. Even if a visitor were to see all four editions, cross-referencing the catalogue and The Folders, they would still inevitably be posed with the missing works that are pointed out. Therefore, if any interpretation through the exhibition is partial, all interpretations are valid.

Quoting Groys, ‘Even though the individual images and objects lose their autonomous status, the entire installation gains it back.’[11] Whilst Solakov on the one hand gives his audience everything possible to make their own interpretations, he also wants to hold the influence of authorship back for himself. A spectrum of control is revealed in his approach, reflecting the editorial constraints of curatorial selection and the potential multiplicity of interpretation achievable by the democratisation of content.

Detail from The Folders (2011)

Detail from Toilettes (2006), remade at Ikon Gallery (2011)

If we accept that art is a powerful mechanism for both representing and influencing politics and culture, then the presentation of art through exhibitions and their supporting materials is a power to be reckoned with. It could be argued, as J.J. Charlesworth has outlined, that ‘presentation’ isn’t a relationship produced between people and certain types of artwork, but is rather a type of relationship between people and an institution; subsequently, ‘the ability to present is itself a form of power.’[12]

Solakov’s meta-curatorial role in his own retrospective, and his strategies of self-archiving and self-historicisation are reminiscent of a variety of different tactics previously employed by artists to reclaim authorship. For example, the movement of self-archiving as a form of corrective action by artists and artist groups from the former Eastern Bloc since the late 1980s; and the advent of self-organised artist-run spaces throughout Europe and the US, since the 1970s. The main motto of Slovenian collective, IRWIN in the 1990s was ‘construction of one’s own context’[13]. Institutional Critique, predominant in the 1960s and 70s by artists such as Daniel Buren and Hans Haacke, and then again in the 1990s, exemplified the various methods employed by artists working within the art institution to highlight what Foucault termed institutional ‘dispositifs’[14]. For artists working in these fields, the common view remains ‘that an artist can curate and that a curator can make art, but – until all artists are in charge of their own personal art space – the categorical distinction between artist and curator remains an institutional one, governed by an inequality of access to resources’[15]. Whilst IRWIN’s publication East Art Map is widely circulated, its acceptance into the cannon of art history has inevitably still been dictated by hegemonic infrastructure (published and distributed by MIT Press).

This struggle over authorship has been an ongoing debate since the emergence of didactic curatorial methods employed by Harald Szeemann and his contemporaries in the 1960s; the curator as auteur[16]. In 1972, Daniel Buren claimed that ‘more and more, the subject of an exhibition tends not to be the display of artworks, but the exhibition of the exhibition as a work of art”[17]. For Solakov therefore the question becomes not how to resist these mechanisms, but how to manipulate them in order to fit his own ideals. As Andrea Fraser claimed ‘it’s not a question of being against the institution: we are the institution’ and therefore the artist’s critical role is to pose a question ‘of what kind of institution we are’[18].

In recent years, a flurry of symposiums, journals, publications, and multifaceted projects interrogating curatorial and institutional practices, have been named a ‘third wave’ of Institutional Critique. These debates have been instigated, not by artists, but by the institutions themselves, aptly summarised in the title of Andrea Fraser’s seminal essay ‘From The Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique’ (2005). The perennial uncertainty of the debate is exemplified by Paul O’Neil’s recent warning that ‘[We] are becoming so self–reflective that exhibitions often end up as nothing more or less than exhibitions by curators curating curators, curating artists, curating artworks, curated exhibitions’[19].

In The Next Documenta Should Be Curated By An Artist (2003), an online collection of written responses by thirty artists, Buren persisted with his criticism of curatorial authorship. The project was intended to give artists a critical and curatorial voice, including them in the discussion around the effectiveness of an artist led curatorial model. The irony however is that the question was posed by curator Jens Hoffman as part of his own curatorial project. By using artists to illustrate his thesis the project takes on a similar curatorial strategy to the one he is criticising, therefore undermining the intention.

It could be argued that artists themselves are in a better position to relay these concerns to a lay audience in a more accessible way, as Teresa Gleadowe commented, ‘the ‘amateur’ status of the artist licenses an intuitive approach and a freedom from curatorial conventions’. San Keller’s project Pre-, Pre-, Pre-, Pre-, Preview at Kunsthalle Fridericianum (Kassel) culminating last April, is perhaps a good example. Through a series of public discussions between him and the curators about the planning of his exhibition followed by what he called ‘digestive walks’, Keller undermined the boundaries of conventional exhibition formats, rendering institutional processes transparent, and had directly incorporated the audience into the development process.

Bearing in mind Solakov’s critical stance, analysis of the exhibition could easily face the same criticism that Institutional Critique came up against in the 1960s and 70s: how can an artist’s practice criticise the compromised position of art within the institution when it exists exactly within this structure? In contemporary debate, a common criticism of artists working in the field is that they and their use of intuitional critique have become part of the establishment[20]. Indeed, Solakov has commented of his own practice: ‘I’m well aware that this is Institutional Critique, but at some point it turned into a situation of ‘I am criticizing you but come on, let me in’[21]. By its very nature, Institutional Critique has always been institutionalised. As Andrea Fraser has argued ‘it could only have emerged within and, like all art, can only function within the institution’[22]. All in Order, With Exceptions therefore has to be read from two different perspectives; on the one hand the artist is subverting the institution, but on the other the institution is embracing this challenge and deliberately engaging the audience in the debate.

Whilst discursive platforms, such as The Next Documenta Should Be Curated By An Artist, have been targeted largely to a specialist audience, many of the key independent curators of the 1990s, such as Maria Lind and Charles Eshe, who were pivotal in articulating curating’s expanded field, have now taken up institutional positions. Their radical, non-exhibition centered and inclusive approach, influenced by the discursive structure of artist-run spaces, has been coined ‘New Institutionalism’.

This ethos has not yet had significant influence on art programming in the UK, possibly due to a limited and populist notion by funders of “the public” as a single entity[23]. Museum Show, part of the Apparatus program currently at the Arnolfini (Bristol), could have proved an interesting comparison. However both exhibition and program fell short of the public discussion that it might have been expected to champion, and instead admitted to focus on an internal exploration within the institution. There are clearly concerns about the role of the art institution in the UK, but it is a contradiction to close this debate both to the general public who use them now or might do in the future.

San Keller, Pre-, Preview, 2011

Since the Ikon’s multi-million pound development in 1995, it has attempted to balance the pressure to be an outpost for a London–centric market, exhibiting ‘star-turns’ to a local public, whilst maintaining its commitment to new models of artistic and curatorial practice.[24] Subsequently, Jonathan Watkins, Ikon Director, feels that ‘demystifying’[25] the institution is a vital component of both curatorial and programming choices, and is crucially part of the Ikon’s on-going strategy ‘to respond to the cultural zeitgeist’[26]. Watkins sees the Ikon’s collaboration with artists and on-going international dialogue as absolutely vital to the organisation’s responsibility to instigate discussion not just around art, but also wider cultural, political and social concerns.

The questioning of curatorial apparatus through All in Order, With Exceptions perhaps falls short of these dialogical practices of New Institutions, where ‘production doesn’t necessarily happen prior to and remote from presentation; it happens alongside or within it’[27]. However, Solakov’s use of synthetic-personalization strategies[28] and a fluid, open-ended structure does at least mean that audience engagement plays a crucial aspect of the project. Overtly open to interpretation by all, it engages both the specialist and the lay public alike. Its layers of interpretation allow the viewer to understand not only the works’ historical and political narrative, but also the curative tensions of selecting from a body of work to represent the artist’s intent. Until funding bodies catch up with the changing relationship between artists, art institutions and the public, All in Order, With Exceptions is exemplary of how exhibitions can open up self-reflective debates to a heterogeneous audience.

—-

[1] Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2000), pp.22-41

[2] Christy Lange, ‘The Self-Preservation Society’, Frieze, October 2007

[3] From Nedko Solakov’s handwritten exhibition text, can be found on the back cover of Jonathan Watkins, (Ed.) Nedko Solakov: All in Order, with Exceptions (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2011)

[4] J.J. Charlesworth, ‘Not about institutions, but why we are so unsure of them’, Nought to Sixty, Issue 4 (2008), Institute of Contemporary Arts, London <http://www.ica.org.uk/16737/Essays/Essays.html>

[5] Boris Groys, ‘On The Curatorship’ in Art Power (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2008), pp. 43-52

[6] Ibid, p. 46

[7] See Boris Groys, ‘Multiple Authorship’ in Art Power (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2008), pp 93-101

[8] From Nedko Solakov’s handwritten exhibition text, can be found on the back cover of Jonathan Watkins, (Ed.) Nedko Solakov: All in Order, with Exceptions (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2011

[9] Interview with Nedko Solakov, 10 January 2012

[10] See Chantal Mouffe ‘Introduction: For an Agonistic Pluralism’ in The Return of the Political (London – New York: Verso, 1993) pp 1-8

[11] Boris Groys, ‘On The Curatorship’ in Art Power (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2008, p 46

[12] J.J. Charlesworth, ‘Not about institutions, but why we are so unsure of them’, Nought to Sixty, Issue 4 (2008), Institute of Contemporary Arts, London <http://www.ica.org.uk/16737/Essays/Essays.html>

[13] Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, ‘Innovative Forms of Archives, Part One: Exhibitions, Events, Books, Museums, and Lia Perjovschi’s Contemporary Art Archive’, E-Flux Journal, Issue 13 (February 2010) <http://www.e-flux.com/issues/13-february-2010/>

[14] The French word dispositif has no single direct English equivalent; it can mean any or all of ‘socio-technical system’, ‘device’, ‘mechanism’ etc

[15] J.J. Charlesworth, ‘Not about institutions, but why we are so unsure of them’, Nought to Sixty, Issue 4 (2008), Institute of Contemporary Arts, London <http://www.ica.org.uk/16737/Essays/Essays.html>

[16] The model of curator as auteur posits the curator as a visionary and the exhibition as their medium

[17] Buren quoting himself in Daniel Buren, ‘Where are the artists?’ in ‘The Next Documenta Should Be Curated By An Artist‘, E-Flux (2003) <http://www.e-flux.com/projects/next_doc/d_buren_printable.html>

[18] Andrew Fraser, ‘From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique’, Artforum, September 2005

[19] Paul O’Neill quoted in J.J. Charlesworth, ‘Curating Doubt’ in Judith Rugg and Michèle Sedgwick, Issues in Curating Contemporary Art and Performance (Bristol: Intellect, 2007) p. 93

[20] For example, Daniel Buren had a major show at the Guggenheim Museum (which famously censored both his and Hans Haacke’s work in 1971) See Andrea Fraser, ‘From the critique of institutions to an institution of critique’, Art Forum (September 2005)

[21] Interview with Nedko Solakov by Iara Boubnova in Nedko Solakov: A 12 1/3 (and even more) Year Survey, (Malmö: Folio, 2003) pp. 73–4

[22] Andrea Fraser, ‘From the critique of institutions to an institution of critique’, Art Forum (September 2005)

[23] ‘Curating with Institutional Vision, A roundtable talk with: Roger M Buergal, Anselm Franke, Maria Lind and Nina Möntman’ in Nina Möntman (Ed.), Art and its Institutions; Current Conflicts, Critique and Collaborations (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2006), pp. 28-60

[24] Claire Doherty, ‘Out of Here: Curating Beyond the Edifice’, in Curating The 21st Century, pp 103-114

[25] The term ‘demystification’ was first used by Seth Siegelaub to describe the curatorial shift in which the space of exhibition was given critical precedence over that of the objects of art

[26] Interview with Jonathan Watkins, 11 January 2012

[27] Alex Farquharson, ‘Bureaux de Change’ Frieze, Issue 101 (2006)

[28] A term in wider institutional mechanisms of mass media and advertising, as described by Norman Fairclough, where a process of addressing mass audiences as though they were individuals through inclusive language usage is used. See Fairclough, Norman, Language and Power (Essex: Longman 2001)