Review: Nottingham Contemporary 24 September to 22 January 2022

ArtMonthly

Nottingham is known as the ‘City of Caves’; the hilly urban sprawl is deeply nestled into its subterranean topology. Cave entrances are visible from roadsides and buildings are cradled by rockfaces. The sandstone bedrock – easily excavated by hand, hardening once exposed – has lent itself to hidden cave networks of pub cellars, dwellings, mines, malt kilns, tanneries and sprawling interconnected tunnels, with a structural integrity that can withstand time. As I have paraphrased from Ithell Colquhoun many times before, the geological underlands of a region mould the surface above creating the backdrop for the human and non-human cultures that subsequently emerge, forming the surface ecologies. Meanwhile, over millennia, the planet’s surface has been contorted to serve human demands: forests giving way to agriculture, farmlands determining ecologies, with urban sprawl, infrastructure and nation state borders, all slicing and dividing. We tend to view the earth with a western colonial perspective, with its human-imagined demarcations of a horizontally flattened surface.

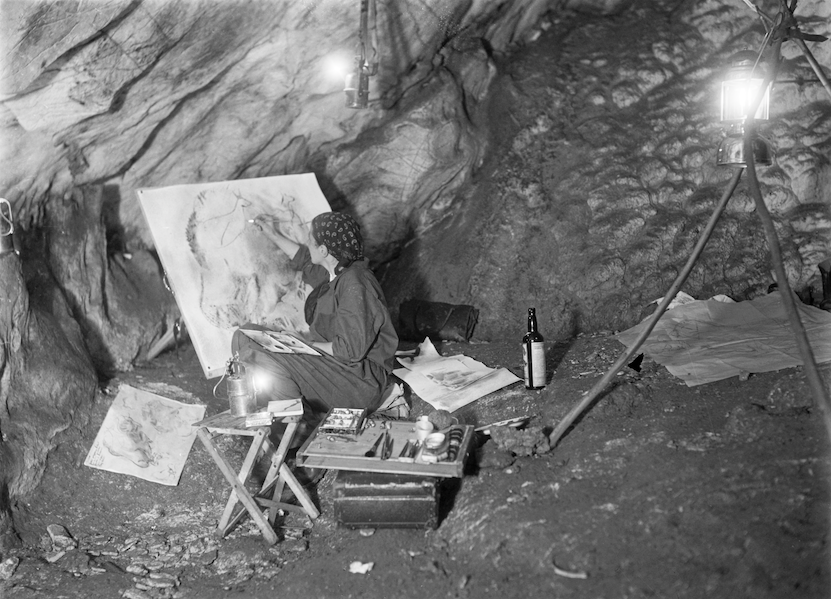

Unlike surface travellers, the speleologist explores terrain independent of these societal and political spatial boundaries, but to delve into geological underlands is also to journey through time, into our material ancestry. The prolific 17th-century Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher described a ‘Geocosmos’, a subterranean world holding ‘the internal economy of the earth and the hidden secrets of nature’. He envisioned that ‘the whole earth is not solid but everywhere gaping’; his wood-cut illustrations criss-cross the planet’s interior with fiery channels, spewing new life out onto the surface of the earth. It is from this frontier of the unknown and unconfined possibility that the artists of ‘Hollow Earth’ each approach the possibilities of thinking with these cavernous depths; as artist Laura Emsley poetically puts it, the impetus is ‘to reconnect to the primordial power of deep earth where our early human minds were first wired’. ‘Hollow Earth’ seek dialogues with the planet’s verticality and, as it reaches downwards through the strata, it reaches into the outstretched history of deep time that is held in the rocky, cavernous underlands hidden out of sight, below our feet.

The subterranean realm has held formative significance in the human imagination throughout our history. From the Greek underworld, Nordic Svartálfaheimr and Christianity’s hell to the Tibetan Buddhist subterranean ancient city of Shamballa, the Hindu underworld of Patala and, in Yakut mythology, the evil underworld of Abaasy spirits, these cosmologies have positioned humanity within earth’s striated depths. The Batagaika crater in the melting permafrost of Eastern Siberia, expanding rapidly since the 1980s, has been dubbed by locals as the ‘Gateway to Hell’ – a terrifying truism of climate devastation. Perhaps because of the anxieties felt from this and other turmoil created by humanity on the earth’s surface, the underlands have received renewed attention over the past century, both from artistic/poetic kinship and the sci-fi apocalyptic imagination, but also more recently from ‘Good Anthropocene’ theorists and, more cynically, developers: the super-rich build underground bunkers while doomsday architects propose elite mega cities in the exhausted craters of vast diamond mines. The subterranean is full of these contentions and frictions. It has been at once a place of salvation and healing, as well as a place of terrifying unknowns and doom. Caves have been a place of sanctuary, escape and retreat, but have also been places co-opted and colonialised. However, and as Caragh Thuring’s fiery billowing clouds of oranges, reds and yellows evoke, truly getting close to the forces that shape our planet is almost impossible. Rather than presenting the cave as a homogeneous subject, offering answers to our time, ‘Hollow Earth’ holds a space for all these contradictions and their multitude of fraught frictions. Steven Claydon’s collection of ceramic vessels using Ukrainian ash, fired in a traditional Japanese kiln called an anagama (meaning ‘cave’), Both Tomb and Womb, 2022, presents a conduit between the temporalities of earthly matter and the fleeting violence of human lifespan; Barry Flanagan’s birds-eye photo etchings depict an optical hole into the ocean as an empty plastic barrel, buried in the sand, is enveloped by the incoming. Both speak to the human invasion and extraction of earth materials, and a human desire to capitalise, transform and exploit, regardless of the impossibly vast forces that nature pushes back with. Elsewhere, Lydia Ourahmane’s vast desert terrains call on demons, extra-terrestrials and lost rivers; while the contemporary echoes through caverns, turning facts into fiction, in Michael Ho’s film Echoes from the Void; and humanoid voices from an unknown era seep through Ben Rivers’s damp cave walls. Plato’s Cave sits in the shadows of many of the exhibitions’ works, subverted and reinvented time and again, where realities are both formed and dissolved.

Over the past decade or two, geologists and cultural theorists have debated the Golden Spikes of the Anthropocene – the deep-time markers of civilisations’ permanent imprint of the planet’s composition – from the Colombian exchange to nuclear fallout and more recently the discovery of microplastics in Antarctic snow. As evoked in Ailbhe Ní Bhriain’s sculptural forms (Profile AM455), however, these taxonomies of geological eras and perceived knowledges of the subterranean create worldviews that are categorisations which both ecology and geology disregard. While historically man has attempted to tame the subterranean through this rationalisation and extraction – whether for precious minerals or enlightenment – the artistic concerns offered through ‘Hollow Earth’ suggest that a more holistic approach is needed. Divided into five sections – The Threshold, The Wall, The Dark, The City, The Deep – the primordial body is imbued in all: the earth is presented as a breathing, permeable body, alive with cavernous wombs of productive possibility, entanglements and melded histories.

In these unfamiliar territories, where our everyday sensory perception is removed, the heightened awareness of the minutiae of touch, smell and temporality offer a new possibility of understanding our own corporeality. This granular collectively is imbued in the hand-sewn work of Flora Parrott’s Cave Map, while other works, created after a ‘darkness retreat’, were formed from a new intimacy with the darkness and a desire to collaborate with it, reaching out in kinship to troglobites of the underworlds – species that evolve in cave ecologies, without ever visiting the surface. From this darkness, Parrott describes how ‘lines between vision, dream and hallucination become blurred’, and new ways of understanding the self, the other and the body emerge. To be in the damp mustiness of the cave is to breathe in deep-time, and to recognise our corporality within the mineral body of planetary surfaces, evoked most poignantly in Emma McCormick-Goodhart’s scents of clays, cave dirts, macerations of mica, cicada moult and the artist’s own Saliva, seeping through our subconscious as we move through the gallery space. Meanwhile, Santu Mofokeng’s photographic series ‘Chasing Shadows’ (1996–2014), depicts the caves of central South Africa, busy with candle-lit rituals. A ceremonial carcass of a goat takes centre stage, while another living goat looks on from a distance; perhaps an analogy of the reality of all organic lives, and the soil and mineral bodies to which we will eventually return.

Reaching down into the subsurface, to hold a dialogue with timeframes that far outstretch the human lifespan, offers a form of stability that is hard to find among the Earth’s contentious entanglements on the planet’s contemporary surface. While ‘Hollow Earth’ presents an aminated survey of artists working with the subterranean as both subject matter and conduit, its significance is one of placement; placing us each, humbly, within a linage of earth’s geological stories and infinite imaginations. The exhibition asks us to come up close; to pay attention to the innate intimacies of exchange that these subterranean worlds have within our surface-based lives.

Sophie J Williamson is a curator and writer based in London and Margate.