Re/generative In-Built Obsolescence

The powdery-grey mouldy orbs in my fruit bowl, which had appeared after a few days’ absence where lemons had once been, reminded me of the ethereal ghosts of the work of Shelagh Wakely. Stored in a lock-up in Kent until we exhibited them for the first time in decades at Camden Art Centre in 2013, fruits, once wrapped in wire frames or adorned with gold leaf, had almost disappeared entirely leaving only the outlined exoskeleton of their former selves. Wakely actively engaged with the fleeting transience of everything: works were washed away with the evening spring rain or rotted as they fed fruit flies; unfired clay sculptures crumbled over time and seeded patterns of fragrant herbs disappeared into a weeded biome in the years that followed. Demonstrating a holistic kinship with the earth and the ever-turning matter of the creations borne from it, her practice traced the shifting behaviour of organic materials and observed their unrestricted natural transformations. Wakely’s artworks exist in the process of becoming through unbecoming, their ephemerality blurring the spaces between inner and outer, the self and other.

Unlike Wakely’s powerful and poetic works, most of capitalist production and consumption demands the ever-new. Begrudgingly, I recently had to buy a new computer as my previous one, only a few years old, already refused to host the software I need to work with. Meanwhile, my inbox is targeted with paradoxical spam of the next-best eco-friendly product to replace all those others that we already have; I don’t need more bamboo socks or plastic-free laundry pods delivered to my door or refillable shower gel bottles. ‘Anyone who believes exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist,’ activist, philosopher and, yes, economist Kenneth Ewart Boulding famously declared to the US congress in 1973. In the same year, German-born British economist EF Schumacher published his seminal book Small Is Beautiful, which over the following decades became the bedrock for the degrowth campaign and the wider green movement. Schumacher’s holistic approach examined our extraction/exploitation-based economic system and its impact on how we live. He did this by bridging William Morris’s ethos of access to good work with diverse philosophies such as Lady Eve Balfour and Henry Doubleday’s pioneering insights into organic farming and the importance of maintaining soil fertility, Lewis Mumford critique of technological innovation and the Industrial Revolution, and Mahatma Gandhi’s anticolonial ethics. Questioning whether economic systems reflect what we truly care about, Small Is Beautiful was revolutionary when it was first published. Sadly, 50 years on it seems that Schumacher’s ideas are still controversial despite their now obvious urgency.

It is still worth asking, however, whether we can turn capitalism’s dependence on inbuilt obsolescence and fast-changing fashions against itself in order to bring it into line with holistic planetary demands. Subverting capitalist value has long been a strategy in art practice, from Gustav Metzger’s Auto-Destructive Art, produced as a counter to the co-existence of cycles of surplus and starvation within the ‘chaos of capitalism and of Soviet communism’, to early net art works such as Google Will Eat Itself, 2005, where a feedback loop of adverts generated income from Google, which was then used to buy shares in the search monopoly to be owned collectively by the public, an ‘auto-cannibalistic model’. The subtitle to Small Is Beautiful is A Study of Economics as if People Mattered; this could perhaps be more aptly recontextualised today as ‘a study of economics as if planetary futures matter’. ‘Any intelligent fool can make things bigger, more complex, and more violent,’ Schumacher wrote. ‘It takes a touch of genius – and a lot of courage – to move in the opposite direction.’ While artists such as Wakely and Metzger subverted the market of capital gain by inverting artistic labour and production, the legacy of their practices are now being redeployed in the context of the climate catastrophe: new tools and strategies, both poetic and practical, are being used to shape more liveable futures.

The unceded ancestorial Sápmi lands in northern Scandinavia have suffered generations of colonial exploitation, extraction and decimation. Artist and activist Pauliina Feodoroff’s family, who are Skolt Saami with roots in Čeʹvetjäuʹrr (in the Finnish part of Sápmi) and Suõʼnnjel (in the Russian part of Sápmi), have experienced deep loss at several levels, from forcible removal from the land for mining projects that destroyed forests and rivers to widespread commercial logging and degradation by acid rain. ‘My whole life has been about trying to survive after those great losses that happened to my grandparents, and they are still affecting our society,’ Feodoroff has said. ‘We lost our lands, our belongings, and our reindeer, and we lost so many of the people.’ Faced with the possible extinction of these communities, Feodoroff redeploys the very tools of capitalism to counter its destructive tendencies: for over a decade, she has repeated her pithy demand, ‘don’t buy our land, buy our art’; now, when a collector buys her work, the money transferred in the exchange is used to buy a piece of Sápmi land with the commitment that it will be cared for by a custodian from the local community. The collector enters into a contract of both personal and legal relations that not only carries critical and contemplative cultural capital (just as a performance work or instruction piece might operate in a collection) but also directly preserves Skolt land and ecology. Feodoroff’s creative practice is inseparable from her work as a land guardian. We were both speaking at a conference last autumn when she understatedly joked: ‘I don’t know why it’s art, but people buy it’; it is the results that matter, not the means. Effectively securing Skolt land and regenerating its habitats, Feodoroff deploys leett (the Skolt duty of care and mutual regeneration) in her practice, rooted in the interdependence of humans with land, waters and other non-human entities. Following in the footsteps of seminal re-greening projects such as Joseph Beuys’s 7,000 Oak Trees for Documenta or Agnes Denes’s Wheat Field next to world Trade Centre in New York, both made 1982, Feodoroff successfully transforms the exploitative, extractive forces of the art market into Sámi epistemologies of reciprocity and care. She also undermines the need for any unnecessary production in order to make the artistic gesture; the production of the artwork and its generative reabsorption into the land is one and the same. The artwork acts simultaneously as an agent of both culture and ecology.

Feodoroff’s works force arts institutions to rethink the ecological commitments of their collections and the future legal and resource responsibility that this entails. While she and others following in this line of enquiry certainly offer hope for the potential of art to transform cultural and institutional practices towards more-than-human care, it is nevertheless hard to imagine a traditional museum collection developing its operational structures towards a position that fits this agenda with integrity. In the Netherlands, Het Nieuwe Instituut offers a promising alternative. Visiting it for the first time a few weeks back, the imposing 1990s concrete, steel and glass building, perfectly positioned next to a reflective geometric lake, doesn’t immediately strike one as an eco-centred enterprise, yet it is the first arts institution to establish what it calls a Zoöp. Initiated by art historian Klass Kuitenbrouwer, the institutional model seeks to foster a regenerative economy: a human-inclusive ecosystem rather than a human-centred one in which all institutional decisions seek to safeguard ‘the interests of all life’. Shaped through research with legal experts, ecologists, artists, designers, entrepreneurs and philosophers, the institute employs a ‘Speaker for the Living’ to represent the voices and interests of other-than-human life in operational decision-making, board meetings and programme activities. This ‘Zoönomy’ proposes a way of learning that is intended to sustain a holistic environment where all living beings are considered in their need for ‘a place to live, food, security, a chance at procreation, a chance at pleasure’. The vegan cafe, where we met for coffee, may now be standard in ecologically minded cultural institutions, but Kuitenbrouwer explains that, although many organisations talk about ecology as subject matter, the Institute is paving the way for ecological regeneration as the ‘central nervous system’ to the organisation’s operational being. In collaboration with multispecies communities in the ground, water, land and air, it situates itself as a supportive member of the ecosystems it participates in, recognising itself as a participant rather than an arbiter, while seeking to transform the institutional economy into a network of exchange of matter, energy and meaning that supports all bodies in their existence.

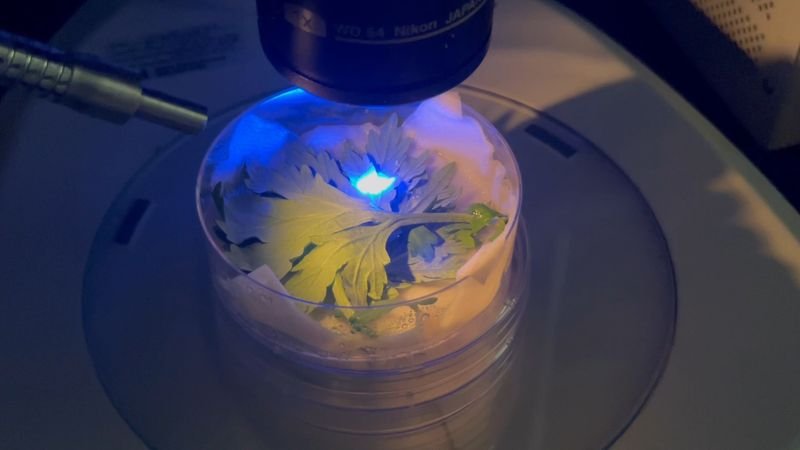

I was recently introduced to the writing of Becky Chambers and her novella, To Be Taught, If Fortunate, which sits firmly in the realm of sci-fi – a genre I would normally pass by – but her idea of ‘somaforming’ is captivating. The protagonist and her space-travelling companions induce themselves into a suspended state as they journey lightyears between vastly different planets; whilst in slumber, biotech slowly morphs their organic composition to suit the new environment to which they will soon arrive: extra enzymes to harness a new biome; blood that produces its own antifreeze to survive extreme temperatures; skin that passively absorbs radiation and converts it into sustenance; stockier limbs and thickened heart on planet with stronger gravity; or ‘synthetic reflectin’ that makes their skin glitter to catch and refracts light on a dark planet. In our Earthly biome, in which our species is saturating the resources we need to survive in it, perhaps we need to start enacting Chamber’s proposal more locally: maybe our future lies in becoming something other than the Homo sapiens we have known until now. In an act of decolonising the anthropocentric and egotistical status of the bounded individual ‘human’, TJ Shin imagines an expanded self for the future, a self that exists beyond one’s skin. Shin has worked with microbiology, yeasts, fungal spores, fermented proteins, mould and other organic membranes as exercises in more-than-human collaboration. ‘Human’ and ‘nonhuman’, ‘life’ and ‘non-life’ are human-constructed concepts: nature doesn’t care about these delineations, and besides, as hosts for trillions of microbes, our bodies have never been entirely our own. Shin recognises these perceived binaries as part of the racial, sexual, gendered and colonial organisation of life, and in recent work has sought to free both themself and their artwork from these constrictions. In recent works, Shin has altered the genome of foraged mugwort by infecting it with the artist’s own DNA, creating not only a being that is no longer completely plant or human and instead a Frankenstein-like composite of vegetal and animal matter, but also a genetic lineage that now lives on in not merely another similar body but another species. While Donna Haraway’s call for cross-species kinship has become a cornerstone for many artists’ practices, Shin pushes this a step further, to coalesce one’s body with non-human species, to consider what it means to live beyond the human species, to ‘de-humanise’ oneself and return to a plant-like, vegetated being.

In their video work Anthropology of a Phytomorphist, 2021–22, Shin explains mugwort is ‘an Asiatic cure or an Asiatic pest, depending on one’s allegiance’; seen in North America as an invasive species from Northeast Asia, it is used in traditional medicines across Asia and Africa as a global biopharmaceutical treatment for malaria. Referencing the philosophical concept of the Pharmakon – a Greek word with two opposite meanings, ‘cure’ and ‘poison’ – the transfused mugwort could be read simultaneously as a ‘toxic poison’ or a ‘miracle cure’. In the shadow of eco-tech projects such as self-maintaining terra0 forests, Shin’s work questions the drive for survival; perhaps regenerative, perhaps destructive. Whichever prognosis, Shin’s work delivers us an image of a future in which human-kind’s anthropocentric binaries are longer to be assumed.

As Feodoroff’s works and the ecologies that they represent exemplify, contemporary capitalism creates a knowledge gap between sites of extraction and consumption, and a blind assumption that we can survive on this planet while continuing in our destructive lifestyles. In ‘On the Poverty of our Nomenclature’, feminist environmentalist Eileen Crist wrote, ‘Scarcity’s deepening persistence, and the suffering it is auguring for all life, is an artifact of human exceptionalism at every level.’ Instead, a humanity with more earthly integrity ‘invites the priority of our pulling back and scaling down, of welcoming limitations of our numbers, economies, and habitats for the sake of a higher, more inclusive freedom and quality of life’. This ethos is at the core of cross-disciplinary architectural designer Xavi L Aguirre’s research into what they call ‘after stuff’, design for a post-commodity future, centred around reversible design and circular loops of production. ‘We’re overstuffed yet there are items in the cart,’ says Aguirre. The contemporary production model – more, faster, cheaper – aligns with the contemporary consumption model that ‘puts spam in your inbox, junk in your mailbox, and makes what is culture today, product tomorrow, and trash the very next day’, which Aguirre concludes ‘has filled up drawers and landfills alike’.

Bridging a conceptual artistic practice with practical design tools, Aguirre attempts to break this cycle of production and consumption that perpetuates both social inequity and climate crisis. ‘A badly bent handrail,’ Aguirre reflected in a symposium last year, ‘a dated teal fridge, a shredded USB cord that lasted me a week, 30 windows from an office building demo, the scuffed side table you threw away last time you moved. Some of these items are likely to still be floating around the world; that fact haunts me.’ Investigating models of material circulation, Aguirre’s projects ask: ‘What if we make no new things?’ Their projects, across art installation, video essays and architectural design, each plan for their afterlife and disaggregation. Aguirre’s installation someparts x useful props, 2021, entirely comprises found materials that can continue to be repurposed, reassembled and imagined for new roles, what they describes as ‘a mixed reality, temporary, mobile and multi-programmable kit’. They prioritise the easy and nimble in their constructions: chunks of abandoned concrete stabilise a modular structure of disassembled steel rig. The simple structures host objects that can perform in different scenarios: something chunky to sit on, something soft to lie on, some sticks to hold things up, some panels for privacy, something tube-like for liquids, something bucket-like to carry things. Refusing new design, the objects remain generic, unaltered and reusable. The components pack down into a kit, ready to move on to another site and purpose: hosting dinners, watching parties, a neighbourhood kiosk, or a nap space at a construction site. Aguirre proposes ways to work with materials that ‘no longer come from the ground but from the muchness that is all around us’, that are ‘extracting value from that which we have already built’. This is a practice that proposes the obsolescence of design itself; producing anew only that which can be deconstructed and repurposed in the future.

Drawing attention to the fallibility of traditionally assumed borders separating artist, product and organisation, Shin, Aguirre and Het Nieuwe Instituut all present a contextually responsive afterlife to the current forms of their works, transmuting and transforming for a changing future, refusing to become the obsolescent detritus of our era, that which Aguirre describes as the ‘trash of tomorrow’. Each of their approaches, though Shin’s most palpably, echo what Mel Y Chen calls ‘transplantimalities’: the symbiosis and kinship with other species according to which human subjects take a ‘tranimal’ turn. Chen describes this as a ‘transness’ between humans, genders and species ‘to account more deeply for their sometimes implicitly mutually enacted politics’ and their relationship to the environments of which they are a part.

Last summer, on a sunny Sunday morning, I met my friend, artist, Anna Zvyagintseva for a walk in the Limburg countryside. We went in search of a stick that she had previously propagated in a bucket of water in her studio, hoping that it had rooted in the ground since she had planted it on the edge of a field a few weeks previously. To Plant a Stick was inspired by the walks she took near her home in Lviv, Ukraine, as a child with her grandfather, who, also an artist, would use sticks to scratch ideas for future paintings into the earth. After he died, Zvyagintseva came across the line of a poem he had copied out by hand: ‘Неначе дерево без листя стоїть моя душа в полях’ (‘My soul stands in the fields like a tree without leaves’). Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, now already a year ago, irrevocably transformed the significance of To Plant a Stick; just as it has changed everything else. It became a work of resilience, transformation and adaptability, regrowing and thriving in a new context; and whilst it has become a symbol for those putting down new metaphorical roots by those who have been displaced through the war, it is also a nod to nature’s adaptability and resilience.

While Shin, Aguirre and Het Nieuwe Instituut each employ transness and as a methods of melding to forge holistic entanglement and cross-species kinship to counter the destructive obsolescent by-products inherent in over-production, Zvyagintseva forcefully exerts this to one of the most insidious perpetrators of destruction and environmental catastrophe: the military. Sustainable Costume for an Invader, 2022, is based on the account of a Ukrainian woman shouting to a Russian soldier: ‘You came here with weapons! At least put seeds in your pockets so that sunflowers will grow when you die on our land!’ A clear plastic-looking jumpsuit, the work hangs against a clean white wall in her studio as if in a fashion showroom. Made from rabbit-skin glue laced with wildflower seeds, the work is an analogy for regenerative possibilities in the face of destruction. Killed in battle, in death the destructor melds with the landscape, re-seeding it for a renewed ecology.

At the end of To Be Taught, If Fortunate, society crumbles on Earth and the space-travelling crew lose contact with the planet; uncertain whether their mission will continue, they induce their next coma not knowing if they will ever reawaken. While Chambers offers a sci-fi possibility for inhabiting new worlds in the distant future, what if instead we could transform human life on Earth now so that it collaborates symbiotically with nature rather than extracts, exploits and destroys? Living is inevitably interwoven with dying; embodied and disembodied; becoming and unbecoming. Now, however, as we live through what Haraway calls the sixth mass extinction, we need to think about rebalancing our biome. We cannot continue to produce art, culture, tech, products, buildings, cities – stuff – exponentially without planning in their holistic end-life, to be reabsorbed back into the biome. Once again, we must change the means of production. As the protagonist of To Be Taught, If Fortunate explains: ‘I have no interest in changing other worlds to suit me. I choose the lighter touch: changing myself to suit them.’